Part 1: Changing systems means changing GOVERNANCE Systems. Read it here.

Thriving and Equitable Systems are Governed by Good Network Design

“At their best, [network] governance systems demonstrate the ideal characteristics of an effective governance entity…. resilience, responsiveness, fluidity, and an organic connectedness to the community and its changing needs.” (Renz, Reframing Governance III, 2020)

Designing network governance systems means addressing an interconnected set of design issues. Governance is not about what we do, it’s about HOW we do everything.

To help social innovators and systems change agents reshape governance systems in line with core values, Circle Forward developed the Network Governance Design Canvas.

This Design Canvas sets up a framework for bringing more clarity to how we function in networks, not as a prescribed set of rules and practices, but as a shared design and meaning-making process for governance that is sensitive to context.

Through coaching and co-design Circle Forward helps networks to understand some of their options in these naturally non-hierarchical network spaces and produce a toolkit for decentralized decision-makers.

The Eight Spheres of Network Governance Design

We owe gratitude to the authors of Connecting to Change the World 1 for the basic architecture of these 8 design issues. The biggest difference is that we define all of these eight as spheres of governance.

Most people come to Circle Forward for help around two spheres that are most obviously about governance: Decision-Making and Agreements + Structure. We created this graphic to help our clients visualize how all of these spheres of governance are interconnected; when you have an inquiry into one issue, you often need to attend to how your network is navigating other spheres to govern effectively.

That said, Decision-Making is the “gateway”; governance designers decide how they will decide, and that links to every other design issue.

For organizations and networks with equity as a core value, we believe that using the the Consent Principle as the basis for decisions helps networks find the sweet spot between equity, inclusion and forward momentum.

This sphere of governance is so key to navigating the other seven spheres that it deserves its own set of articles including this one: Consent-based Governance is a Great Choice for Collaborative Networks. Here’s why.

Creating the conditions for authentic consent provides the architecture for systems that can no longer ignore the needs of whole groups of people. Alexis Flanagan says: “Consent is a bedrock norm that applies just as much in governance [and the violence it has perpetuated] as in domestic or sexual violence.”

Click here to learn more about how practicing Consent creates efficiencies and builds trust.

Most of the decision-making habits we all inherited reinforce and replicate inequity. These habits can be deeply entrenched in our culture and our own practices. This is why we created Cultivating a Culture of Consent workshops and coaching for groups who are ready to start experiencing the results of Consent-based Decision making directly as these game changing practices become a part of your culture.

The quality of decision-making depends on the coherence of the Purpose. Purpose and Strategy are at the center in this diagram – as they are in every initiative. These provide the touchstones for creating enthusiasm for Participation and Resourcing, as well as developing the initiative’s Agreements and Value Propositions. Without coherent purpose and value, collaborations can turn chaotic or fall apart.

When testing for people’s consent with a course of action, you are asking people to sense into what is out of their Range of Tolerance in relation to goals. When people who are impacted by issues participate in authentic ways, their goals shape the strategic direction.

We help your team to sense into and shape the strategic frameworks that will serve as useful touchstones for participants to find coherence together, as an initiative, to achieve what no one person or organization could achieve alone.

Driving the Purpose (and Strategy) is Evidence + Learning. Graphically, this sphere is the leading edge of governance, and there is a kind of infinity loop between the two. Effective strategies start with a scan of the landscape, and as strategies are implemented, learning happens, and that in turn improves the strategies, and so on.

At the same time, what we understand as evidence and how we make space for learning are fraught with equity issues. The Chicago Beyond Equity Series, Volume One, “Why Am I Always Being Researched?” names “seven inequities standing in the way of impact, each held in place by power dynamics.” Governance is a key leverage for shaping the dynamics of power.

When we are open to it, seeking equity among multiple “ways of knowing” transforms our understanding of what is possible, what is good strategy, and how we approach the work.

‘The question “Who decides?” connects the sphere of Decision-Making to the sphere of Participation.

In a network structure, it is not sustainable for one person to be the hub. John Winnenberg, network manager for Ohio’s Winding Road, recounted how he had taken leadership in the organization early on. Tracy coached him how to get more buy-in and to encourage more people to take leadership roles. “I was able to move from being the pivotal person, to having a lot more hands on deck,” he says.

The validity of decision-making is directly tied to equity and to which stakeholders are participating and guiding direction. Flanagan asserts, “Network governance gives us practices for more distributed leadership, which sets up conditions where people most affected by issues have a voice in deciding what needs to happen next. We ask, ‘Who do we need to get advice from, who else should we test this with for consent?’”

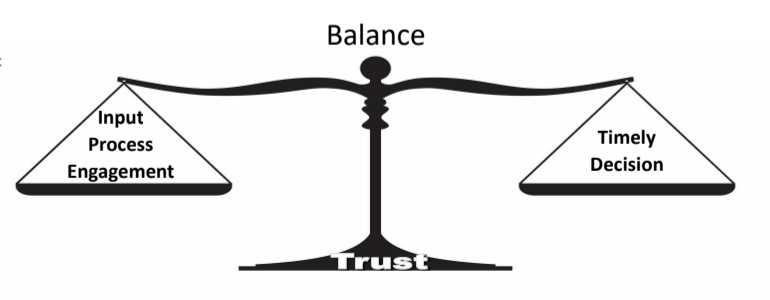

In a dance of bridging polarities, consent practitioners learn to balance a level of inclusion that produces wise decisions, with timeliness of decisions, as seen in this graphic created by Loyd Platson, Regional Co-chair of The Alliance in Alaska.

While listening and adjusting for the range of tolerance of participants, decision-makers across the network cultivate a willingness to take imperfect action that is “good enough to try, safe enough to fail.” They know that, in an adaptive consent-based culture, there is always the opportunity to revisit and adjust plans if unintended consequences become evident. Decisions guide the work until they are deemed not effective given new circumstances and information.

With so much riding on participation, initiatives must be able to deliver tangible value to participants. People want to know, “Is this worth my time?” Initial complaints that “This is taking too long” often subside once people perceive the value of having more participants involved in decision making.

Nicholai Joekay, an Alaskan Native, agrees:

“In the beginning, I was very resistant to the process. It took more time, having to be in consent. When I realized it led to greater equity, I finally exhaled and went along with the process and saw that it is a good way to do business. The way the Alliance has adopted this process will change the way we operate all our systems. I hope so, because we need this type of inclusivity in every aspect of our government, especially provision of services.”

One key practice that supports decentralized leadership and action is to form teams around clearly articulated Aims — statements about what teams are working together to create and for whom.

These Value Propositions keep a team focused on their Purpose; become a communication tool for attracting Participation; and become an accountability tool for Evidence + Learning about how well the aim was met.

The connections between Equity, Decision-making, and Participation show up most acutely when making decisions about Resourcing. Resource flows shift when equity is operationalized and those most impacted by decisions have a voice in decision-making. Consent-based processes are designed to uncover gaps in awareness and to weave diverse perspectives into wiser decisions.

Joekay sees that more resources are coming in since beginning to work with consent based decision-making, especially to rural communities. “The Alliance and these processes have put rural Alaska on the map, with a face and a voice,” he affirmed.

This is mirrored in the internal operations of the Resonance Network, “The dominant culture assigns more value to the director than to other staff. But our ancestors lived by sacred reciprocity,” Flanagan says. “We talk about salaries openly. The question is, ‘What do you need to thrive?’ within the range of what’s possible.”

Governance includes “the processes of interaction and decision-making…that lead to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions.”

Norms are the standard habits of behavior that define a culture. In most cases, norms are implicit, the water we swim in (like the image above from dRworks) Operationalizing equity means making the invisible visible, and codifying new behaviors, and that’s what this sphere of governance is about.

The Resonance Network is choosing its norms intentionally. As Flanagan says, “When a problem arises, we can ask: ‘What dominant culture habits are showing up, and what can we do instead?” For example, “if there’s an inequitable distribution of labor, we stop the work until that is resolved.”

As we intentionally create new norms, we practice embodying them in ourselves and in relationships. We codify them in graphics and documents that form touchstones for how we have agreed to work together. This includes staffing structures for coordination, shared leadership practices, and operating principles, often with graphic visualizations, so that these can be easily shared and translated for different audiences.

A unifying narrative brings coherence to the work as people move in and out of the network, and emerges out of the work of Purpose, Participation, and Evidence+Learning.

Internally, networks need effective communication platforms that invite participants to connect and work in relationship to one another. Authentic participation and communications depend on operationalizing the value of transparency.

But simply making large amounts of information available is not sufficient to achieve transparency. Participants need well-designed communication portals where they can find and access information that is timely, accurate, and meaningful — including the information they need to make decisions — without information overload.

Networks piece together communications ecosystems that build in redundancies across different communications tools, knowing that not everyone is going to access the same tool. This includes real time meetings (in-person or on zoom) and phone calls, email updates and newsletters, as well as digital collaboration apps, like Google and Slack, that allow people to work asynchronously (i.e. not in the same place and time). It also includes long-term memory archives; we think of files, but additionally, the people who carry an initiative’s history are beloved resources.

How do we put this into practice?

Embedded in Network Governance Design Canvas is the knowledge that governance design is NOT a linear step-by-step process.

Hope Finkelstein of the Alliance asks, “How do we take the next steps?” It is an iterative process, observing, listening, and making adjustments. “As in plumbing, you turn the water on; the infrastructure must be tested for ‘leaks.’ That indicates the next steps.” It is an appreciative inquiry process, as participants focus their attention on noticing and cultivating the practices that already embody the values, while shoring up the gaps.

This is something that Flanagan believes her organization is intuitively doing. Their work with Circle Forward is focused on making their norms and practices more transparent, and on supplementing what’s working really well with consent-based processes, agreements, and structures.

Putting consent into practice means being humble in recognition of our gaps in awareness, and we all have them. Testing for consent is a step intended to reveal these gaps and mitigate negative impacts before taking action. The range of tolerance gives people a framework for naming “objections” they may sense.

A good example of this was a “culture clash” that Flanagan experienced in an early meeting of the Resonance Network with Circle Forward facilitators: “What came up was habits of white supremacy culture, the habit of being in the head more than the body, deferring to whites.” Navigating with consent, Flanagan says, “people were able to speak from their whole selves, without apologizing — this was a game changer! The conflict provided a learning and growing opportunity, as we saw each other’s humanity. The women of color saw that they could resist norms of white supremacy, and hold a boundary with the facilitators about RN’s norms — staying in our bodies, bringing the whole self, valuing “being” as much as “doing.” It was a moment of deep learning and connection, affirming our values.”

There are no “simple steps” to transforming culture.

This work will take time, it may be the work of multiple generations, although it does bring satisfying results in the near term, too.

“Those on the fringes finally have a voice and equal standing with everyone else, especially in a statewide coalition,” says Joekay. “It’s refreshing to be front and center…. The rural voices are getting heard, this is very promising. When we have a process with inclusivity, we can handle these divisions.”

1Connecting to Change the World: Harnessing the Power of Networks for Social Impact, Peter Plastric, Madeleine Taylor, John Cleveland

2The Governance Analytical Framework, Mark Hufty, Graduate Institute of Geneva

Contact us

We’d love to hear about your work.