The Consent Principle

We receive a lot of questions about consent-based decision-making, and sometimes hear confusion from people when they practice it. A very basic misunderstanding is that consent is a particular kind of meeting process that looks like everyone sitting in a circle making group decisions. And, a lot of people are not in consent with every decision being a group decision!

So, they ask us, “Does every decision have to be a consent decision?”

But as far as consent…well, we ask,

When do you want to use your power to force people to do something against their will? How effective (or ethical) is it for someone more powerful than you to act in a way that ignores your concerns?

After more than a decade of practicing consent, we offer our learning here.

We receive a lot of questions about consent-based decision-making, and sometimes hear confusion from people when they practice it. A very basic misunderstanding is that consent is a particular kind of process that looks like everyone sitting in a circle making group decisions. And, a lot of people are not in consent with every decision being a group decision!

So, they ask us, “Does every decision have to be a consent decision?”

We say not every decision has to be a group decision.

But as far as consent…well, we ask,

When do you want to use your power to force people to do something against their will? How effective (or ethical) is it for someone more powerful than you to act in a way that ignores your concerns?

After more than a decade of practicing consent, we offer our learning here.

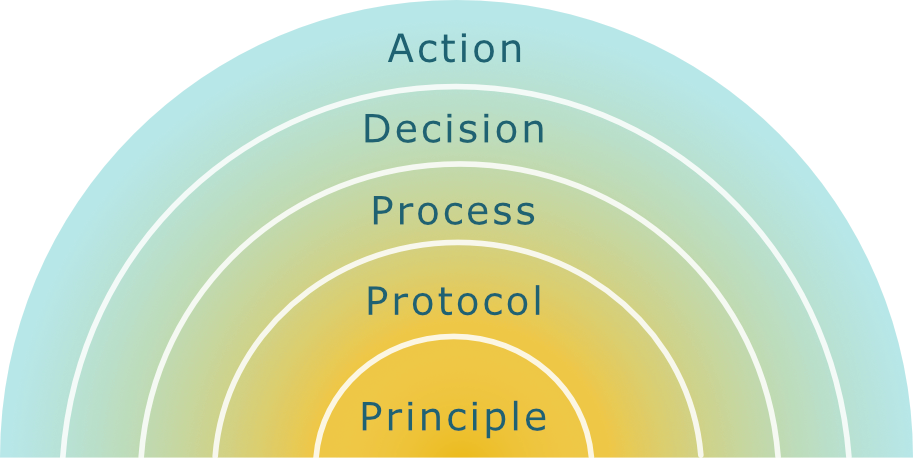

Consent is a Principle, Not a Process

Consent is a principle, not a process. Like informed consent when practiced in the physician-patient relationship; it’s grounded in respect for autonomy, transparency, and the right to self-determination.

A legal definition of consent is: When a person voluntarily and willfully agrees to undertake an action that another person suggests. This is the spirit of true collaboration. It’s why practicing consent as a principle for decision-making can be such a game-changer for organizations and networks seeking justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Our Consent Protocol is designed with the wisdom of legions of community organizers, who take time up front to build relationships and trust. This protocol can be used in different ways at different times. Some decisions are far-reaching and can benefit from a range of processes for engagement. Other times, decisions have much lower impact, and the processes can be minimal.

Creating the Conditions for Consent-Based Governance

The traumatic effects of the dominant culture in schools, workplaces, policy arenas, and other decision-making spaces, is that many of us are conditioned to not expect consent.

The Consent Principle in governance starts with an assumption: that the most wise and effective action addresses what is meaningful to the people most impacted. The movement for people with disabilities said it simply: “Nothing about us without us.”

The most effective decisions have buy-in and support from those who are responsible for carrying out decisions, as well as those who are impacted. Because, people who were not bought into the decision can withhold their support and actively or passively resist it. Problems that were ignored in the beginning can be costly to fix later. Future opportunities can be lost when trust or relationships are sacrificed.

And, no one person or entity has the full picture. Everyone has gaps in awareness or understanding. So, living in consent is a practice in humility, communication, and listening – among those who are responsible for decisions and carrying them out; those with the power to affect them; and those who are impacted by the results.

Overcoming gaps in understanding is never complete. But, one of humanity’s winning strategies is cooperation. In the practice of the consent principle, we develop systems leadership; we become more aware of the complex and diverse dynamics in any system.

Sometimes the practice of the consent principle might take the form of simply asking people for their advice, as described by LaLoux in Reinventing Organizations. When community members-at-large are impacted, there may be several stages of engagement tools and processes. However, the consent principle does not necessarily require “getting everyone around a table,” which is often impractical. It does require people responsible for decisions to take time to identify, and be transparent about, who is included in the process and how.

Just hearing each other is not enough

Practicing consent requires flexibility and adaptation. It is a practice of co-creation, which takes an ability to hold multiple and contradictory viewpoints, and to be open to more than one way of addressing a problem. Consent is found in actions that are good enough to try, safe enough to fail.

Efficiencies develop over time as people learn what works; clarify roles and boundaries; openly address conflicts; hold on to healthy power and let go of control; and build trust. When people trust their important concerns will be addressed as best as possible, they tend to (paradoxically) delegate more authority and autonomy to individuals day-to-day.

Research has found that trust reduces the amount of communication time and effort. As Stephen Covey famously said, work moves “at the speed of trust.” The practice of finding consent for action builds trust, and trust eases the practices of finding consent.

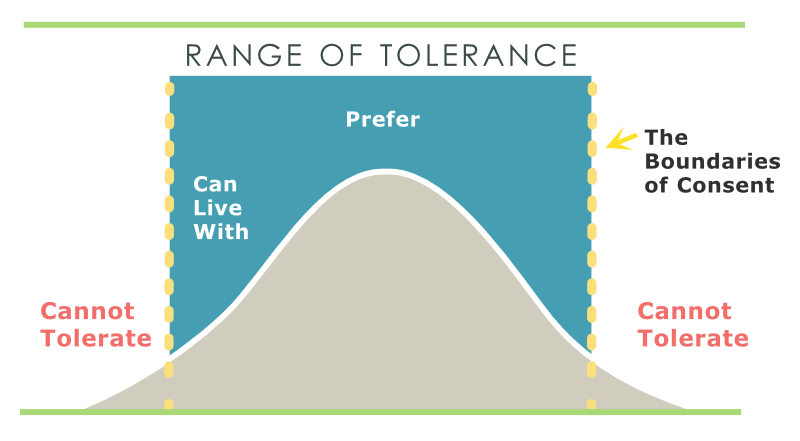

The Consent Principle, as we learned it from sociocracy, means that a decision is made when no one impacted by the decision has any significant objections to it.

By objection, we mean no one can identify a risk that we cannot afford to take. We appreciate our colleague Nate Whitestone for this added clarity.

An objection is valued in consent-based culture. It is an insight about a risk of something that might lead to unintended consequences. A risk typically involves conflicts with the stated purpose or strategies. It might be a condition that makes it very hard for a member to perform a role. Under those conditions, a group or person would be out of their range of tolerance.

The shared intent is to listen to people who dissent, understand the risk they are sensing, so as to adapt. To get the benefit of our diversity, even if we do not agree it is a risk, decision-makers adapt to find solutions that address the objection, while staying within their own range of tolerance. Again, nobody has the whole picture and everyone has gaps. With practice, we spend less time debating and more time learning about the complexity of a situation — while sustaining forward momentum.

Ecosystems of Consent

One of the benefits we’ve experienced in our consent practices and processes is something that feels like the regeneration of socio-cultural-ecosystems. The range of tolerance is an ecological framework. We can think about an ecosystem’s range of tolerance through the example of a trout in a mountain stream.

A trout can live and thrive with some variation in conditions. But, if the water gets too warm or too cold, for example, the trout will not survive or reproduce. We say, “The trout cannot tolerate the conditions in the stream.”

To have something as glorious as a mountain stream full of trout requires that conditions meet the range of tolerance of all the interdependent parts of the system.

Our organizations and networks are systems. To thrive, we need conditions that meet the range of tolerance of all parts of the system. We also need governance and decision-making that integrates diversity with equity. If we want to regenerate our natural socio-cultural-ecosystems, we can use use the framework of the range of tolerance as a tool to apply the Consent Principle.

Circle Forward equips collaborative leaders and social innovators with the skills, tools and practices to collectively navigate “VUCA” conditions (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) toward a regenerative future.

We’d love to hear about your work.