Is top-down always the most effective way to manage? Roderick Simmons, Director of Asheville’s Parks & Recreation, does not think so. In fact, he believes that “as government we must change, or we’ll just repeat the mistakes of the past,” he says.

The department oversees more than 50 parks, offering golf, swimming, tennis, skateboarding, roller hockey, basketball, a climbing wall, velodrome, nature center, playgrounds, community centers, tennis courts, ball fields, picnic shelters, and trails; plus a wide range of programming for all ages. It is perhaps the most public facing department in the city, interacting with numerous diverse communities who want to have a voice in the decisions that are being made about public facilities and resources.

Problems with trust, disconnection and capacity

One of the problems the department faced was mistrust in the communities, especially those such as Asheville’s Southside neighborhood that have long histories of marginalization, and are often most in need of the services. This creates a perception of conflict between residents’ and city staff’s goals.

Simmons wanted to find a way to engage with the public that would shift power to a collaborative public engagement process that could create a new dynamic of shared ownership and buy-in.

At the same time, internally, staff had felt disconnected from each other, working across many different locations. In the absence of an effective structure for integrating the different functions and facilities of the whole department, people were working in their own silos. This made decision-making much less informed, coordination clunky, and the department less responsive to change. Just as important, a portion of staff were contributing below their potential. There were not clear pathways for taking initiative or expressing leadership. The bureaucracy encouraged a “Just tell me what to do” attitude, and projects could languish for years without completion.

Simmons knew that he needed the department to be functioning as a more integrated whole system.

Enter Circle Forward

Simmons set out to create a more inclusive and adaptive operational structure, so that all the different people who were affected by or responsible for decisions, could be engaged in the process, rather than just the few top managers in City Hall. And, he wanted a structure that was flexible and responsive in a very dynamic environment. He met Tracy Kunkler and Michelle Smith from Circle Forward Partners. Circle Forward is a system of practical tools and processes that enable organizations and networks to design their own adaptive and collaborative governance systems around theConsent Principle.

The Consent Principle

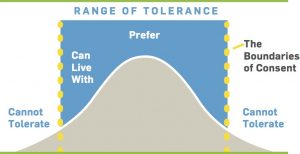

“The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when none of the group members has any significant objection to it,” says Kunkler. “In a culture of consent, we recognize that all the different people in a system have access to different kinds of information about risks. An administrator with access to the operating budget understands certain kinds of risks that a decision will create, while program staff in direct contact with the public will understand other kinds of risks generated by that same decision, while community members themselves see another aspect of the picture. It is when we aim for keeping the whole system within its ‘range of tolerance’ that we enable really wise decisions.”

“Taking this one step further,” Kunkler continues, “in a complex and dynamic environment, the consequences of any decision are sometimes not known until it is implemented. So, organizations are seeing themselves less as machines churning out results, and more as living systems, that are always learning, adapting and responding to feedback from the environment as they go. An organization that operates with consent is designed to listen for feedback about concerns that are raised from any person in the system, and to have the tools to respond and adjust.”

A Better Practice for Making Decisions

“We have a management team of about 30 people who all took the Circle Forward training,” says Debbie Ivester, the assistant director. “Before Circle Forward, the 5 or 6 managers in City Hall made decisions affecting the whole department and the information would trickle down.” Sandra Travis, a program manager, describes that experience: “ In the past we might not even know, with everyone so scattered, that there was one person who didn’t like the decision that was handed down. They would be talking to other staff saying, ‘This is crazy!’ And by the time we would hear it, it would require a lot of damage control, trying to figure out who all is unhappy and why. That took a lot of time. So we see consent as a timesaver over all, even though it feels time-consuming at first. You find out right away if someone has a problem, and you tweak it. We are all equal, this is true democracy.”

Says Mark Halstead a program manager, “We learned that consent is not the same as everyone agreeing, but that everyone can support the decision. It’s ‘within their range of tolerance,’ to use Circle Forward’s language. I might ask someone, ‘When you’re out in the field and someone asks you about this, will you be on board?’ If not, you’re out of consent, and we need to adapt the decision to the point where it addresses your concern.”

“I think consent is a great practice.” Simmons says. “Even though it’s not a perfect system, it creates a dialogue. Everyone’s on the same page. And for that, the process is efficient – it helps us to focus on the conversation, stay centered, and make decisions. And everyone is accountable: because we all decided on this proposal, it’s not just one or two people, it’s a group effort, each one holding each other accountable.”

Building Capacity

According to O’Neill and Brinkerhoff, in their book “5 Elements of Collective Leadership,” success in an organization “depends on the leadership within the entire group rather than the skills of one person. Without the gifts, talents, perspectives, and efforts of many people, sustainable change is difficult to achieve.” On the other hand, “Creativity is unleashed as people tap into their fullest abilities and capacities.” The larger and more complex the organization, the truer this becomes. Instead of feeling burdened, managers can distribute responsibility. People who formerly felt underutilized are able to contribute, meeting their needs for purpose, mastery, and autonomy. When collective leadership is present, the authors believe, people take true ownership of the results. “In the past, staff would bring an idea to a program manager to implement.” says Travis. “Now, the idea person becomes the project lead.” She mentioned a facilities supervisor who is about to launch a mobile phone app for the department.

According to Ivester, in the past there had been a lack of structure for moving projects forward, so that sometimes, money was not spent and a project did not get accomplished even in 3-4 years. “Now, there is a team, not just one person assigned,” she reports. “The project manager breaks down the action steps. We’re charting it out and we’re all holding each other accountable, we can all see and track the progress. We can now collectively know how we’re moving work forward, and know what the next six months hold. Projects are completing. This is a major difference.” Simmons adds, “We rotate among the staff so that everyone has an opportunity to be on a project team. I want staff to get more expertise in projects, such as writing a grant proposal, which some of them have never done.”

“This is capacity building in two ways,” say Halstead. “It’s capacity building for the department, because we are tapping the talent we have, and it’s also building capacity in that employee’s skills and leadership. Building capacity means getting more done with what we have, so we are better stewards of the public’s money. A bond approved last year means that with the same number of people, we have more to do. We’ve increased our connectivity, and our ability to make decisions efficiently. Having employee leadership and involvement at all levels will make us stronger.”

And, he notes: “There’s more responsiveness to the public, by enabling and empowering those who have direct interaction with the public.”

Engaging the community

“Police, fire, sanitation are pretty straightforward services,” says Simmons. “But Parks & Rec are more about quality of life, health, community building. My interest is to change the way we interact with the public. We have to change relationships, not just get more information.”

He says, “With neighborhood service planning, we have started engaging the public differently in decision making. We don’t want to create win-lose situations anymore. It’s only win-lose if you’ve made up your mind already. Simmons continues: “For example, in Southside, we did a community input piece, asked the residents how they would like a whole set of facilities to be.

Now, we’re evaluating the input we received, and hiring a consultant to look at what’s feasible, and what is not, at this site. We are not just going to make a top down decision about it. If we just say ‘This is what we’re doing,’ people will push back. Instead, we will bring back all the ideas, the ones that won’t work for technical reasons, that are out of our hands, and the options that will work. We will present the facts, the options, so that the community can make an informed decision. It takes a long time, it’s tough to keep everyone engaged. But, when we find a good solution that is within a range of tolerance, it’s a win-win situation based on the merits. And, we build good relationships for the future,” he concludes.

Challenges

“It’s been a challenge for people at management level to change the way we made decisions,” admits Halstead. “Some staff were used to having decisions made for them; we had to keep pushing them to be part of the decision making process.” And there’s still some hesitancy to speak out. “Every group has the pressure to conform.” says Christy Bass, a program manager. “And the project teams are an opportunity for development, but I’m not sure everyone fully views them that way yet. People want to know what they’re signing up for, and how much extra work will it mean?”

It took time to truly incorporate the new processes, which felt awkward at first. Ivester says, with a rueful smile, “I thought I was the only one not getting it. You can talk the theory, but putting it into practice…” While the nearly 30-person management team was forming, their first six meetings included Circle Forward training plus agenda planning meetings in between. It took time for managers to gain facility with the process. According to Bass, “Intention doesn’t mean getting there as fast as we can, but making the best decisions as we go. We often need a lot more feedback and input; how are we challenging ourselves to be patient, get that feedback, process it and then move forward?”

Culture Shift

Changing from a hierarchical, single-leader model to a living systems model with collective leadership is a major shift in culture. “I try to remember that this is about culture change.” says Simmons.

His own leadership style is changing to be more patient. “Before we make decisions we need to put structures in place. I keep telling our staff, not everything is an emergency. So let’s plan ahead and take time to do things right. We need to remember that, most times, we can choose the timelines. Not everything is a sprint. We have time to discuss things. Projects will come and go. We miss opportunities anyway even when we rush. We’ll get more efficiency in the long run, even if we miss a deadline right now.” He adds, “Engaging people in a process has its own energy, it’s alive. I’m learning to let that flow happen, without trying to steer or direct the outcomes, knowing it will be a decision by the whole. It will be a more sustainable decision. I’m not falling into the old habits of saying what we are going to do. Even when staff asks me what I want, I ask, what do WE want? Anyone can make a proposal.”

Says Bass, “Recently we had to deal with an issue that arose that had an impact on the whole department. Roderick slowed us down. We’re now responding, not reacting. Before we can make a decision, we need basic information. Who’s affected? If we fund one thing, which other thing doesn’t get funded? And are we all OK with that? That ripple may go further out. Roderick went around the room just collecting the questions. When those 11 questions are answered, that may prompt more questions. This is creating a healthy, robust conversation. Knowing we have employees on the line who want an answer, management could give a quick answer now. But instead, we are weighing the options, everyone will make the decision together, with the same information available to all. That’s why it’s slow. We’re bringing everyone along. Everyone has a chance to ask their questions.”

Says Halstead, “We want people to make decisions on every level so it doesn’t all have to come from the top. Of course there are some decisions that have to go to City Council, there is still a hierarchy involved, but at some levels we can make decisions. People are more willing to speak up and trust that they know the answer.”

Travis: “It’s less easy for a few to dominate a meeting. People who were quiet before, now speak up. Everyone has an equal say when we’re sitting around that table – not just Roderick or a program manager. That’s a radical departure.”

“We’re more aware of seeking everyone’s input, because what they have to say is valuable”, according to Halstead. “This is a change in attitude; we’re all equal in there. In the past, if top management was not present, the meeting would not take place; now, the meetings happen even without them and decisions can still be made. It takes time to change culture. To really have people involved, you have to do your best to live it daily, and over time trust is built, and takes root.”

Contact us

We’d love to hear about your work.